Hidden Homework (updated 2021)

When I was teaching at NYU, every year I ran a prototyping class where students make a new game every week, starting with a prompt or constraint that I give them. It became a tradition for me to hide one of their prompts inside a small, prototype-scaled game. Ostensibly it was to give them some inspiration and benchmark the right amount of work for a 1-week prototype, but really it was just fun for me to design a game which people will be forced to play to the end. It’s an unusual reward structure to work with: if you beat the game, your reward is homework!

For me, a good prototype expresses a single idea or tests a single hypothesis, so a prototype is actually a great container for a creative prompt, which typically takes the form of a single encapsulated concept or provocation.

I did that for seven years in the end, so this is a little time capsule of some of the games I made.

2015 was the first year I made one of these prompts, at Doug Wilson’s suggestion. The game is a simple physics game, a reinterpretation of the speed-skating from Epyx’s C64 classic Winter Games. Downward pressure from the skates on the ice is converted into forward momentum, which would be easy enough were it not for the hazards of the ice rink.

Made in the old version of Ruby Bergstrom’s Luxe, which used to be a rather lovely Haxe library and is now on the way to becoming a rather lovely Wren library. I don’t mind either way; I’m not a good enough programmer to have opinions about languages. Whatever library or language I use, it seems to lend its own flavor to the work you make with it. I don’t want a single tool that I can use for any game… I want a digital toolshed that looks like Depeche Mode’s synth collection.

In 2016 I got interested in optical illusions and op-art, and I made Zebra, an optical maze. Mazes are not the most interesting gameplay element if you’re relying on intrinsic motivation — they’re just not very entertaining — but if there’s some sufficiently compelling extrinsic motivator I think their irritating properties become quite interesting. Made in Unity, which is pretty great for making 3D prototypes.

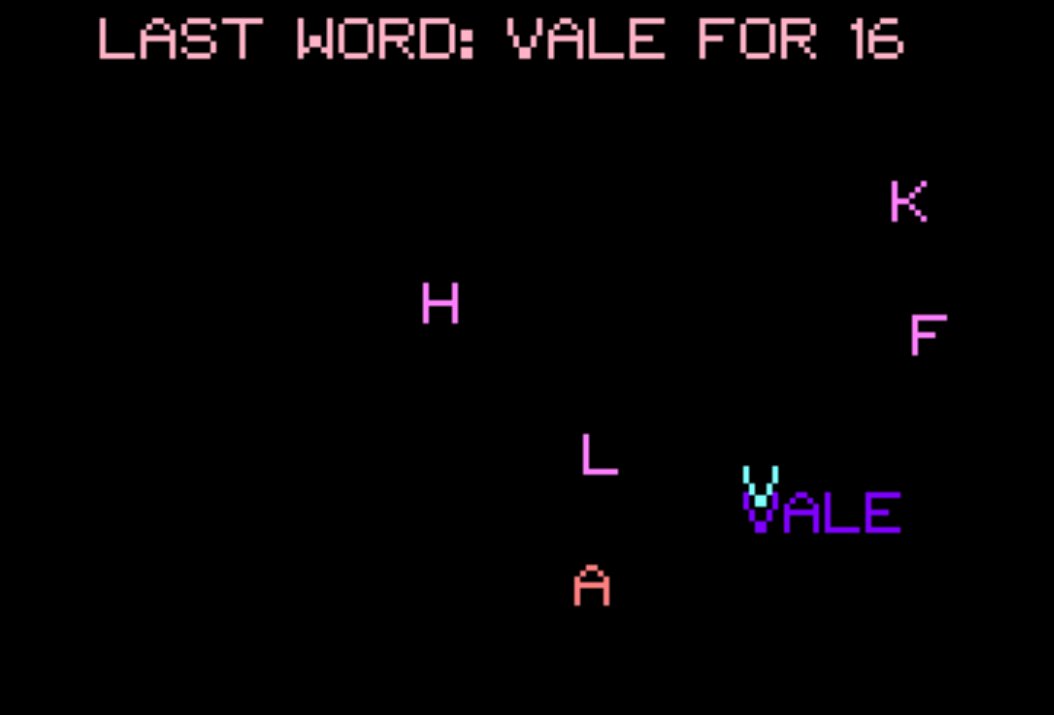

For 2017 I made Last Word, a little action word game where the difficulty increases as your words get longer. There’s a proper videogame version (with no prompt hidden inside it) here. Made in Terry’s Haxegon engine, a nice ultra-minimal Haxe library which is perfect for small prototypes. I love using engines that build to the web as well as native targets – makes it very easy to share prototypes without asking the player to do anything more annoying than play the actual game (which might already be quite annoying, honestly).

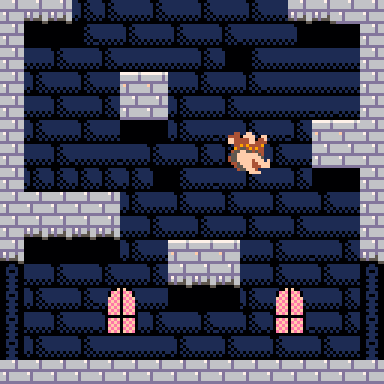

This is 2018’s assignment, a diabolical puzzle. You’re a monk who has forgotten where his cell is in the monastery, and who must walk the labyrinth in order to remember it. If you can find his room, you’ll find out what the assignment prompt is. I was a bit worried the students would be unable to find the prompt hidden in this one, but about half of them got there eventually. (The rest were expelled from the university.)

2018’s class was 100% Pico-8 so it seemed appropriate that the prompt game should be in Pico-8 too. Pico-8 is so great for prototyping — as a case in point, it builds to a single JS and HTML file which loads quite happily in the browser from a local file, so you don’t get annoying permissions or crossdomain problems.

For 2019 I ran two prototyping classes – one in Pico-8 for the undergraduates and a graduate version with no platform constraint (which generally means they work in Unity). So this year I hid the same prompt in two different interpretations of the same idea. I tuned the Pico-8 game for the youthful reflexes of the undergraduate class, but I did not count on the fact that none of them would have ever played a bullet-hell game, and as a result, only one of them was able to reach the end and find out what the assignment was. I instructed that person that they could keep it a secret if they wanted to.

Play AlleyRat | Play AlleyStrat

For 2020 I started the semester with a prompt in the form of a multiplayer jigsaw puzzle game – the students had to reconstruct an image with the prompt hidden in it, with no clues, working simultaneously. Unfortunately, as I presume you’re reading this alone, it doesn’t really make sense to share that one – but it looked like this:

Untitled sixteen-player jigsaw puzzle.

The second hidden-homework prompt for this year is this 3D Maze game, similar to the ‘Zebra’ game below. Visually speaking, it’s an homage to Paul Woakes’ Commodore 64 classic, Mercenary.

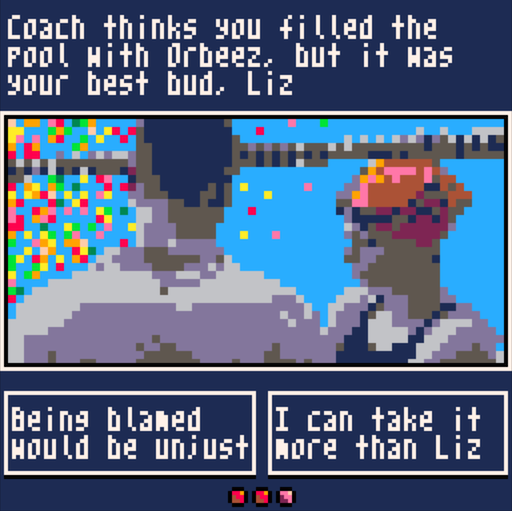

In 2021, the last time I taught the class, I didn’t want to hide the homework in the games. Instead I used the games as ways of presenting ideas. I made several, but I like this one, a reinterpretation of the fortune-telling minigame from Ultima IV.

For my very final prompt, I wanted to leave the students with one lasting idea: that I make games for enjoyment and want to do it as much as I can, even when I’m limited to a day or two’s work and 8192 Pico8 tokens. I hope that came across in this little game.